| ISBN13: | 9781517912703 |

| ISBN10: | 1517912709 |

| Kötéstípus: | Keménykötés |

| Terjedelem: | 304 oldal |

| Méret: | 216x140x25 mm |

| Súly: | 482 g |

| Nyelv: | angol |

| Illusztrációk: | 34 black and white illustrations and three maps |

| 0 |

Indigenous Archival Activism

GBP 108.00

Kattintson ide a feliratkozáshoz

A Prosperónál jelenleg nincsen raktáron.

Who has the right to represent Native history?

The past several decades have seen a massive shift in debates over who owns and has the right to tell Native American history and stories. For centuries, non-Native actors have collected, stolen, sequestered, and gained value from Native stories and documents, human remains, and sacred objects. However, thanks to the work of Native activists, Native history is now increasingly being repatriated back to the control of tribes and communities. Indigenous Archival Activism takes readers into the heart of these debates by tracing one tribe’s fifty-year fight to recover and rewrite their history.

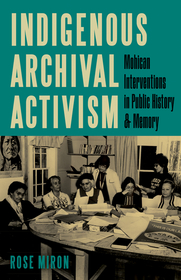

Rose Miron tells the story of the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation and their Historical Committee, a group of mostly Mohican women who have been collecting and reorganizing historical materials since 1968. She shows how their work is exemplary of how tribal archives can be used strategically to shift how Native history is accessed, represented, written and, most importantly, controlled. Based on a more than decade-long reciprocal relationship with the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation, Miron’s research and writing is shaped primarily by materials found in the tribal archive and ongoing conversations and input from the Stockbridge-Munsee Historical Committee.

As a non-Mohican, Miron is careful to consider her own positionality and reflects on what it means for non-Native researchers and institutions to build reciprocal relationships with Indigenous nations in the context of academia and public history, offering a model both for tribes undertaking their own reclamation projects and for scholars looking to work with tribes in ethical ways.